A New Paradigm for Social Work: The Critical Realist Perspective

Understanding the Layers of Reality to Transform Theory, Practice, and Education

If you’re a social work student or practitioner, you’ve probably been steeped in a range of theories—systems theory, attachment theory, social learning theory, and humanistic theory. You’ve spent countless hours learning how to apply these to real-world situations, analysing cases, and imagining how these frameworks help you understand your clients better. But as I moved from university to professional practice, I noticed something quite unexpected. Despite all that learning, I wasn’t using these theories as much as I thought I would, especially those rooted in a positivist way of thinking.

Attachment theory, social learning theory, and systems theory all come from a positivist tradition that emphasises empirical research and observable behaviours. For instance, attachment theory relies on observable behaviours to define attachment styles and predict developmental outcomes, while social learning theory focuses on how people learn behaviours by observing others. These theories often imply that the "problem" lies within the person and that by changing certain behaviours or relationships, we can "fix" them. This perspective assumes a somewhat mechanical view of human life, where everything is observable, measurable, and predictable.

But the more I practiced, the more I realised that people’s issues are rarely just about them as individuals. Often, it’s the broader social, cultural, and structural factors impacting their agency—their ability to act and make choices—that shape the difficulties they face. It’s these deeper layers of reality that we often miss. This is where critical realism comes in.

Historical Context and Philosophical Underpinnings: The Rise of Critical Realism

Critical realism was developed by the British philosopher Roy Bhaskar in the 1970s as a response to the limitations of both positivism and interpretivism in understanding the social world. Bhaskar argued that both of these dominant paradigms were fundamentally flawed. Positivism, with its emphasis on observable phenomena, often reduced complex social realities to mere patterns of behaviour or correlations, missing out on the underlying structures that generate these patterns. Interpretivism, on the other hand, focused too heavily on subjective meanings and experiences, often neglecting the broader, objective realities that shape these experiences (Collier, 1994).

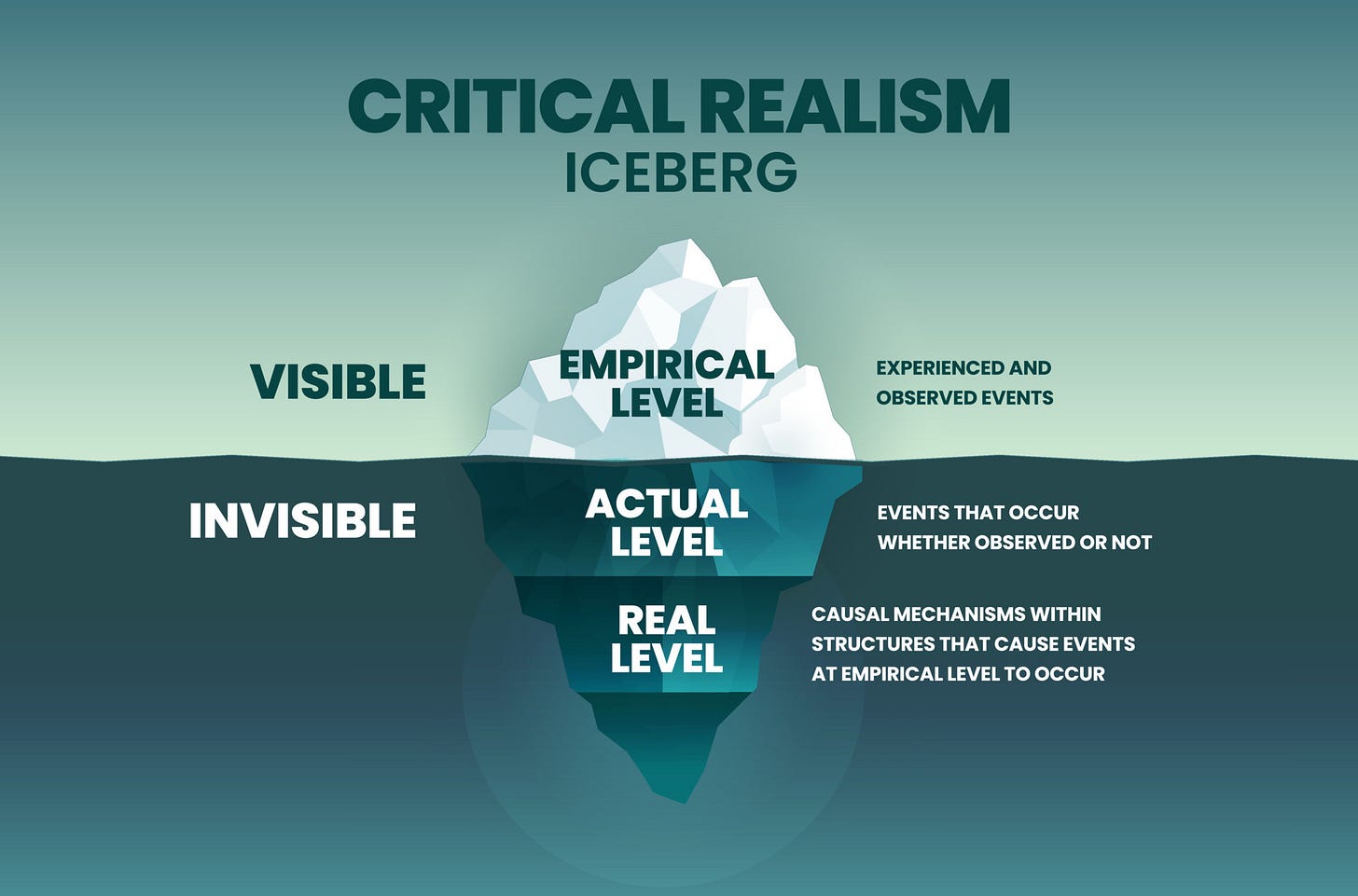

Bhaskar’s critical realism offers a middle path. It rejects the idea that we can only know what we can observe directly, proposing instead a layered ontology that distinguishes between the empirical (what we experience), the actual (what happens whether we experience it or not), and the real (the underlying structures and mechanisms that cause events). This stratified view of reality allows for a more nuanced understanding of social phenomena, recognising that what we see on the surface is often just a glimpse of much deeper processes at play (Collier, 1994).

By breaking away from the idea that social science should emulate the natural sciences with their focus on regularities and predictability, critical realism acknowledges that the social world is inherently complex and shaped by multiple, interrelated layers of reality. This makes it particularly suited to fields like social work, where understanding the interplay between individual experiences and broader social structures is crucial.

Philosophical Relevance: Why Critical Realism Matters for Social Work

So why does all this matter for social work? Critical realism’s focus on ontology (the study of being and reality) and epistemology (the study of knowledge) is especially useful in addressing the complex, multi-layered nature of social work issues. Social work is not just about understanding individual problems; it’s about understanding how these problems are shaped by various social, economic, cultural, and political structures.

Consider a social worker dealing with a family experiencing housing instability. A positivist approach might focus on the family's behaviours or their immediate environment to understand the problem. An interpretivist might delve into the family’s subjective experiences and meanings around homelessness. A critical realist, however, would go further, asking: What are the underlying mechanisms causing this housing instability? Is it due to broader economic policies, local housing market dynamics, or cultural factors such as discrimination? Critical realism allows social workers to explore these deeper layers, providing a fuller picture of the challenges at hand and, more importantly, potential pathways for change.

Implications for Social Work: Key Concepts and Applications

Critical realism introduces several key concepts that can transform how social workers understand and engage with the social world:

Emergence: This concept refers to the idea that new properties or powers can emerge from the interaction of different elements. For social work, this means recognising that individual behaviours cannot be fully understood in isolation from their social contexts. For example, a young person's involvement in crime might emerge from a complex interplay of family dynamics, neighbourhood influences, educational opportunities, and broader economic policies. Understanding these emergent properties helps social workers identify more effective interventions that target not just the individual but also the wider social conditions that contribute to the problem.

Stratification: Critical realism’s stratified ontology is crucial here. It helps us see that reality operates at different levels—individual, social, and structural. This is important because it encourages social workers to consider not just immediate or visible issues (like a child’s behavioural problems) but also deeper, often invisible, structural issues (like poverty or systemic racism) that shape these behaviours.

Causal Powers: Unlike positivist approaches that look for regular patterns or correlations, critical realism focuses on understanding the causal powers—the capacities of entities to act in certain ways. For social work, this means asking not just “What is happening?” but “Why is it happening?” and “What are the conditions that make it happen?” Understanding causal powers allows for a more targeted approach in social work interventions, where the aim is to change the conditions that give rise to problems rather than just addressing the symptoms.

In practical terms, these concepts help social workers move beyond a narrow focus on individuals to a broader analysis that includes the structural and cultural conditions impacting their lives. This doesn’t mean discarding existing theories altogether but rather expanding our toolkit to include a deeper understanding of the underlying social forces at play.

Looking Ahead: Embedding Critical Realism in Social Work

This article is just the beginning of a series where we will explore in greater detail why critical realism should be embedded into social work practice and education. By embracing critical realism, we can better prepare social workers to tackle the complexities of the real world—moving beyond surface-level interventions to engage with the deeper, often hidden, mechanisms that shape social life.

Breakdown of the Upcoming Series:

Article 2: Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice

Objective: This article will examine how critical realism helps bridge the persistent divide between theoretical frameworks and practical application in social work.

Structure-Agency Relationship: We will delve into Margaret Archer’s Morphogenetic Approach to understand how critical realism provides a framework for understanding the interplay between social structures and human agency over time.

Practical Implications: Real-world examples from social work practice will be used to show how critical realism can facilitate the integration of theory into practice, such as in case assessments, interventions, and reflective practice models.

Pedagogical Strategies: We will discuss teaching methods that incorporate critical realism in social work education to prepare students for real-world complexities, such as scenario-based learning or critical case study analyses.

Article 3: Critical Realism and Anti-Oppressive Practice

Objective: This piece will unpack how critical realism aligns with anti-oppressive frameworks, advancing more equitable practices in social work.

Content Expansion:

Analyzing Power and Inequality: We'll explain how critical realism’s stratified ontology helps uncover deep-rooted power structures and social mechanisms that sustain oppression.

Case Studies: Detailed case studies will illustrate how critical realist approaches have led to deeper understandings of, and responses to, systemic inequalities in areas like mental health services, child welfare, or community-based social work.

Theoretical Synergies: We will explore the synergies between critical realism and other critical theories, such as intersectionality and post-colonial theory, to enrich anti-oppressive practices.

Article 4: Promoting Critical Reflexivity in Social Work Education

Objective: This article will focus on how critical realism can be used to foster critical reflexivity—a crucial competency in social work education.

Critical Reflexivity Defined: We’ll break down the concept of critical reflexivity from a critical realist perspective, emphasizing the importance of understanding both one’s own positionality and the socio-structural contexts that shape practice.

Pedagogical Tools and Techniques: Specific tools, such as reflective journaling, critical incident analysis, and dialogical methods, will be detailed to help develop critical reflexivity in social work students.

Impact on Practice: We will analyse how critically reflexive practitioners are better equipped to address issues like practitioner burnout, ethical dilemmas, and the evolving needs of service users.

Article 5: Research Methods and Epistemology in Social Work Through a Critical Realist Lens

Objective: We will analyse how critical realism informs a distinctive approach to research methodology and knowledge production in social work.

Mixed-Methods and Methodological Pluralism: We'll discuss critical realism's promotion of mixed-methods research to capture both the depth (qualitative) and breadth (quantitative) of social phenomena.

Depth Ontology in Research: Concrete examples will be provided to demonstrate how critical realist research designs operate, focusing on retroduction and the search for causal mechanisms rather than mere empirical correlations.

Critical Realism vs. Other Paradigms: We will compare and contrast how critical realist-informed research fundamentally differs from positivist and constructivist approaches, particularly in how evidence is generated and interpreted in social work research.

Article 6: Enhancing Policy Analysis and Advocacy in Social Work

Objective: This article will explore how critical realism strengthens policy analysis and advocacy, offering a more nuanced approach to understanding and influencing social policies.

Critical Policy Analysis Framework: We will introduce a critical realist framework for policy analysis that considers underlying generative mechanisms, structures, and agentic actions.

Case Examples: Examples will illustrate how a critical realist approach has been employed in advocacy work, such as challenging austerity policies or advocating for inclusive mental health services.

Advocacy Strategies: The discussion will focus on how critical realism can inform strategic advocacy, aligning both micro-level (individual client advocacy) and macro-level (policy advocacy) efforts for systemic change.

Article 7: Preparing Future Social Workers for Complex Challenges

Objective: This piece will focus on how critical realism equips future social workers with the analytical tools to address the ever-evolving challenges in the field.

Complexity and Contingency in Social Work: We will analyse how critical realism’s recognition of complexity, contingency, and emergent properties prepares practitioners to adapt to rapidly changing environments.

Curriculum Recommendations: Suggestions will be offered on how to integrate critical realist principles into social work curricula, including interdisciplinary courses, collaborative projects, and community-based learning.

Future Directions: The article will reflect on emerging global issues, such as climate justice, digital social work, and transnational migration, and how a critical realist approach can provide innovative insights and solutions.

Article 8: Conclusion – The Future of Social Work Education with Critical Realism

Objective: The final article will synthesise the series and propose actionable steps for integrating critical realism more thoroughly into social work education.

Critical Realism as a Transformative Paradigm: We’ll summarise the potential of critical realism to serve as a transformative paradigm in social work education, practice, and research.

Future Research and Collaboration: The conclusion will encourage further research and cross-disciplinary collaboration to advance the critical realist approach within social work and allied fields.

Call to Action: We'll end with a call to action for educators, policymakers, and practitioners to embrace critical realism as a robust framework to navigate the complexities of contemporary social work.

By the end of this series, you'll see how critical realism provides not just a new lens for understanding social work but also a powerful tool for transforming practice and education. Stay tuned!